There’s a stream in the central Cascade mountain range, not too far from the bustling metropolis of Seattle, that has occupied many of my daydreams over the past year. Somewhere buried in an old scientific report was a single stream name, noting a genetically pure population (no prior hybridization with rainbow trout) of westslope cutthroat trout. It also included a small image of some of the most brilliantly colored cutthroat I had seen from Washington waters. I knew that I would need to plan a proper trip here and discover if it still held these native trout.

The westslope cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki lewisi) is a subspecies that fascinates me for a variety of reasons. As the species (clarki) and subspecies (lewisi) would suggest, the trout was first officially described by the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1805 with Meriwether Lewis noting in his journal:

“…precisely resemble our mountain or speckled trout in form and the position of their fins, but the specks on these are of a deep black instead of the red or goald colour of those common to the U.’ States. these are furnished long sharp teeth on the pallet and tongue and have generally a small dash of red on each side behind the front ventral fins; the flesh is of a pale yellowish red, or when in good order, of a rose red.”

The speckled trout that he’s referring to there is the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) native to the Midwest and Eastern US. The westslope cutthroat caught during the expedition were reported to measure between 16 and 23 inches and would help to supplement many of the crew’s meals throughout Montana, Idaho, and Washington.

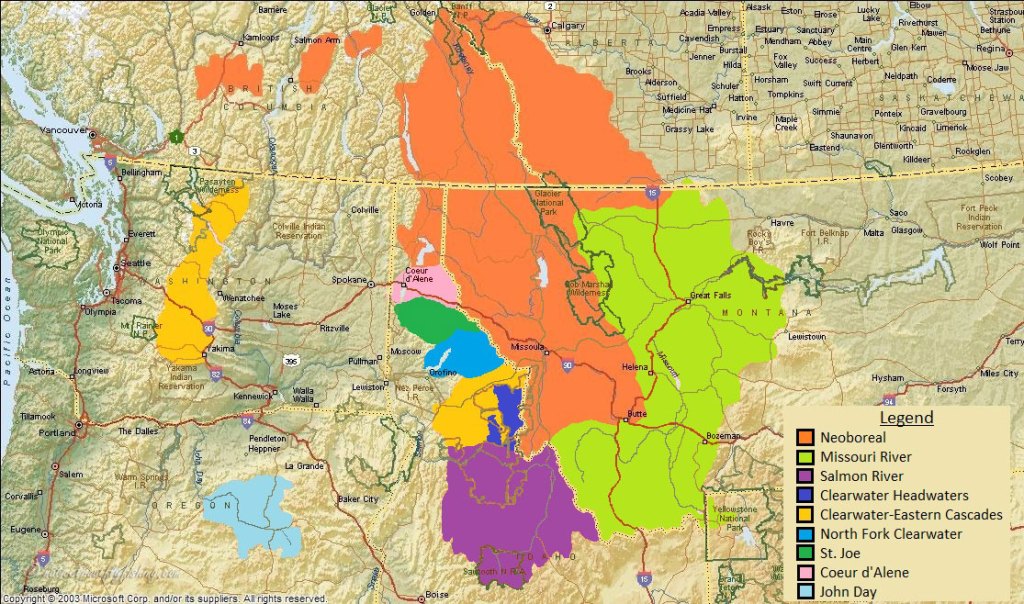

Much like trout, our understanding of them is something that continues to evolve. In 2018, a group of researchers published a paper outlining the framework for a new system of westslope cutthroat classification. The paper proposes upgrading the status of the westslope cutthroat from subspecies to species designation with 9 genetically distinct subspecies therein. This is just one piece of an entire proposed “redesign” of the cutthroat lineage as we know it, an approach that is genetics based as opposed to the current largely phenotypic based system. While not (yet) formally accepted by the American Fisheries Society, I find this new classification extremely intriguing as it would increase the number of unique subspecies from 14 to 25! (the idea of the San Juan cutthroat as a unique subspecies is also a part of this proposed reclassification). As such, the proposed subspecies native to the Cascade mountain range of Washington is the Clearwater-Eastern Cascades westslope cutthroat.

I first encountered the westslope cutthroat last fall in the North Cascades. Although technically the same subspecies, there are two important distinctions between these two experiences. The first is that the population in the North Cascades were lake dwelling. Besides the phenotypic differences between stream and lake dwelling populations, primarily size and coloration, the population in the alpine lakes likely originated from stocking efforts along with rainbow trout. Because of this, the lake largely consisted of westslope cutthroat/rainbow trout hybrids (known as cuttbows). This stream resident population is different in the sense that they have called this tributary their home since the Pleistocene and do not have a history of hybridization with rainbow trout.

To call the body of water a stream would be stretching the definition of the word. It is actually a tributary of a tributary of a stream. A true headwater stream, and the type of environment I had been in search of ever since arriving in the Evergreen State. I knew that headwater streams that held native cutthroat like these were out there, hidden trickles high up in the mountains. Like many good things, they were only to be found through sweat and exploration.

I had devised a plan for such exploration using an app called onX Backcountry. I use this for both planning and as a source of on-trail navigation on all of my trips and would highly recommend it for any activity that takes you off of the pavement. I had marked two waypoints in particular that had piqued my interest. The first was a point where the trail nearly intersected the river and located along topographical lines that were indicative of a somewhat flat section. This in turn would act as an indicator for the conditions at the second waypoint further up the stream, which is where the trail would first cross the stream and where I had planned to access it.

On a Saturday morning in late July, I departed early and headed east towards Seattle and the Cascade mountain range. A little over an hour later, I would get my first glimpse at the stream where it crossed a back road. As I had expected, it looked quite narrow and brushy. The visible portions were a series of steep cascading falls emptying into small plunge pools. These pools likely could contain trout, but both sides of the road were heavily posted for trespassing. I didn’t have the best feeling that this stream would provide accessible opportunities, but still I remained optimistic that a flatter section may afford the longer pools and runs to sustain a healthy trout population. This could only be found by making the hike.

Staring down the start of the trail head-on, I knew that this wasn’t going to be easy. The brush was heavily overgrown on both sides leaving only a narrow corridor for passage. It was unavoidable but to make contact with the brush on both sides as I moved forward, and the tall, dense vegetation ahead gave me little visibility to potential animals (namely bears). To be honest, it was quite scary! Feeling my heart starting to beat faster, I stopped and asked myself aloud “what are you afraid of Sam, Bigfoot?” Ironically, this trick worked as the idea of a Sasquatch tumbling out from the brush seemed as hilarious as it did preposterous; my fears were immediately put to rest. Determined to reach my destination, I trudged onwards.

At just under a mile, I knew that I would soon be approaching the first of the GPS waypoints that I had marked. I could hear the sound of rushing water growing ever louder as I drew nearer. Standing at the spot of the digital X, I could see no sign of the stream but rather a primitive looking side path appeared to cut down towards the water. I followed it and was in complete awe of what I found at the bottom. There emerged a picturesque waterfall emptying into shimmering pool. I took in these sights while contemplating about setting my rod up and giving the pool a few casts. As tempting as it was, I decided that I would keep moving forward and return if the upstream portion didn’t pan out.

To say that it panned out would be an understatement. Upstream about a half mile or so, I found one of the most pristine sections of a small stream that I have had the opportunity of fly fishing. Small to medium sized cobblestones lined the creek bed that wound through beautiful rifle-pool-run successions. The tall surrounding evergreens provided the necessary refuge from the sun while still affording a sense of expanse. It was more than even my daydreams had envisioned.

Filled with both relief and excitement, I strung up my 3wt fiberglass rod with a small, bushy elk hair caddis and studied the first run. A small pocket of slower water about the size of a dinner plate looked promising as did the main channel flowing through the undercut bank to my left. Placing my caddis imitation in the slower pocket water, it passed through 3 or 4 times untouched. On the next cast, I watched as a dark shadow rose from the bottom and sipped the fly ever so subtly. With a raise of the rod tip, I was tight to it and wrapped my arm around the back of my pack for the net. Soon I was scooping the first trout of the day, a beautiful and tiny native westslope cutthroat. A series of dark navy oval parr marks lined its body, with a faint redness in the cheek plate that laced its way through the markings. I photographed and released the trout back to its quiet pocket, overjoyed at the confirmation that this stream did indeed hold a population of native westslopes.

The trout seemed to grow progressively more brilliant in color as I worked my way upstream. The largest of the trout displayed under bellies of bright orange, signifying sexual maturity. Observing the wide range of coloration and patterns between each cutthroat is fascinating to me, with each one as unique as a fingerprint. The colors that these trout displayed were even more stunning than the photo in the report that had led me to this stream. In total, I brought about a dozen of these native gems to hand.

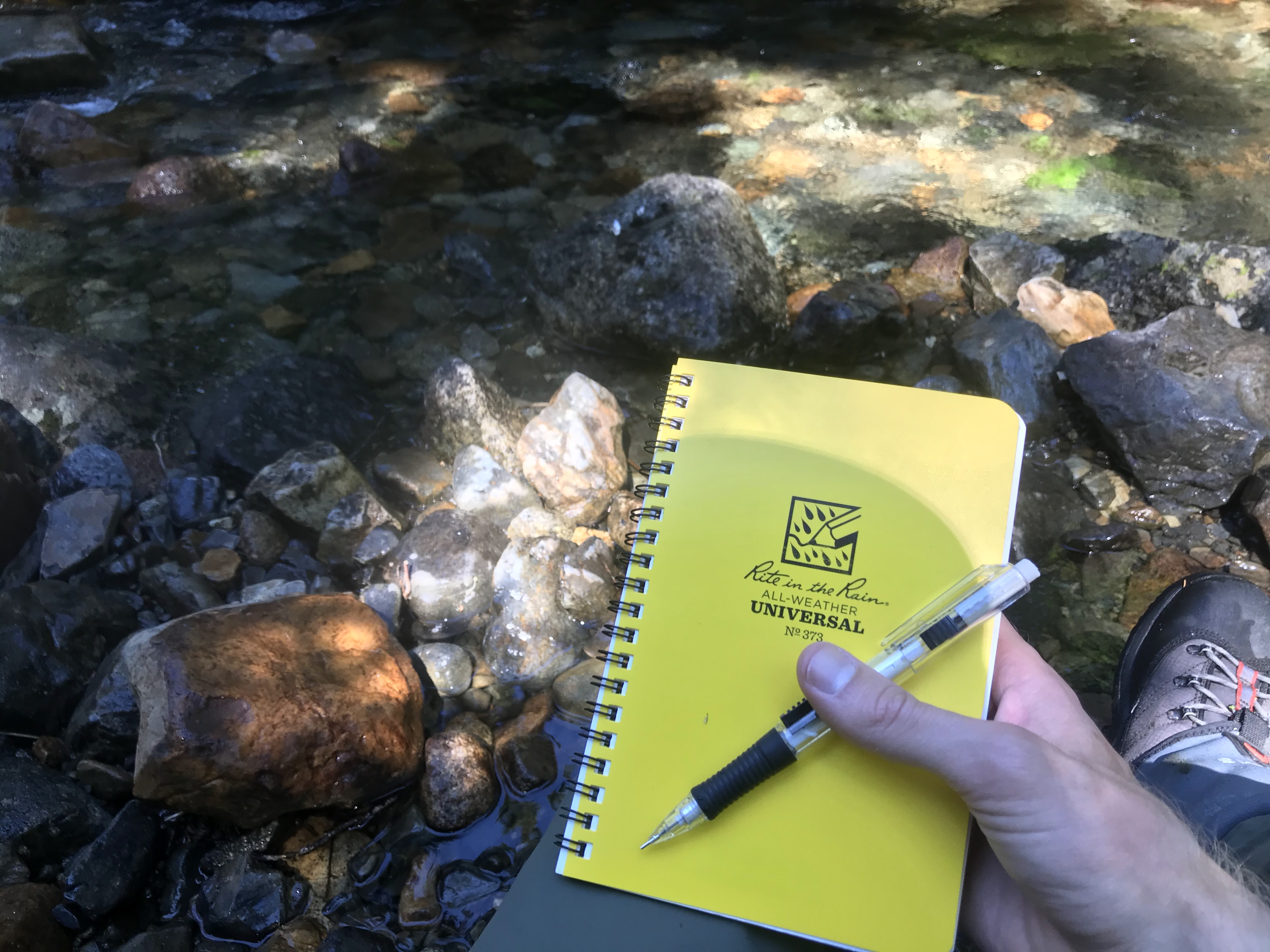

Eventually I reached the end of the flatter portion of the stream as the topography grew ever steeper. My GPS confirmed the transition to higher gradients ahead. I sat down on a moss covered rocks beneath a cluster of fragrant bluebells (Mertensia paniculata) and pulled out the contents of my lunch from my backpack; a tuna packet, dried mango slices, and a Clif bar. I ate and journaled while observing the pool directly ahead of me. The return hike seemed to pass by quickly, as I replayed each section and trout of the day through my mind. I contemplated returning to fish the waterfall pool on my hike out but decided it was best to leave that for a future trip.

I departed the trailhead and headed towards the main branch of the Tacoma Public Library. I wanted to view a book that they had in one of their special collection rooms, the 2nd edition of Patrick Trotter’s ‘Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West’. At 560 pages, it is an absolute tome on the evolution, biology, and taxonomy of all of the known species and subspecies of cutthroat trout. It also happens to be an exceedingly rare book, with WorldCat indicating that only some 300 libraries and universities around the world own a copy. Copies on the open market are even rarer yet.

Upon arriving at the library, I was disappointed to learn that I wouldn’t be able to view the book because I had neglected to set up a formal appointment to use their reading room. I spent some time discussing my intentions for viewing this particular book to the librarian and she graciously agreed to allow me 20 minutes of reading time with it! (I imagine her internal reasoning to be somewhere along the lines of, “this 20-some year old man wants to view a reference book on trout, what’s the worst that could possibly happen?”)

It felt a bit like the scene from National Treasure where Nicholas Cage is in the National Archives getting a few minutes alone with the Declaration of Independence, except instead of inspiring words from our founding fathers, I was handed Mankind’s collective knowledge of cutthroat trout and the 20 minute timer started. I quickly flipped to and read the chapter on westslope cutthroat trout to supplement my research for this post. After the 20 minutes were up, I handed the book back to the librarian and continued on my way home. Since my visit to the library, I ended up triggering on a reasonably priced used copy on eBay. I believe that it will be an invaluable tool in my quest to deepen my understanding of these fascinating creatures.

Reflecting on this trip, I believe that it instilled in me some level of self confidence that I did not possess prior. Perhaps some of the overgrown and scary looking paths that we approach in our life aren’t all that scary, even if we take them alone. Maybe there’s a hidden waterfall along the way. Maybe there’s even some westslope cutthroat trout waiting for us at the end.

Discover more from The Path Less Fly Fished

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sam, you are truly an amazing writer!! I felt like I was right there with you!!!

LikeLike